Despite the litany of sins levelled at the automobile- it’s woeful energy efficiency, harmful pollution, congestion, road casualties, damage to public space, contribution to obesity- we are still wedded to the car. In the UK the car accounts for over three quarters of trip miles. The flexibility, security and door-to-door convenience of automobile travel remains a winning combination, particularly when we spent most of the 20th century developing car-based cities with limited alternatives.

Current planning practice restricts car travel to improve sustainability and urban quality of life. Short of an outright ban however, the car is here to stay in some form or other.

For the automobile to be in any way sustainable we need to radically challenge current systems of car design, driving and ownership to effectively create a new mode of transport. This post considers whether such a revolution is possible in light of exciting recent innovations.

Electrification

We now for the first time have competitive alternatives to the internal combustion engine car on the market with electric and hybrid models from the world’s biggest manufacturers. These technologies dramatically reduce or remove tail-pipe emissions. Surely then the eco-car has now arrived and city transport has been saved?

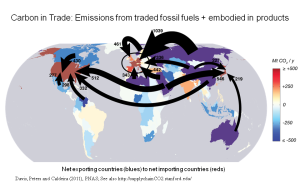

Well… as electric cars (and vans/taxis/buses) become more widespread urban air quality should improve dramatically, as should vehicle mileages. But as we generate the majority of electricity using fossil fuels (and will continue to do so for the next 20 years+), CO2 emissions from electric cars remain significant.

Furthermore several other car design issues are not solved by electrification, such as energy used in manufacture, road congestion, safety and damage to public space. There’s a danger that electric cars become merely a green-wash cover for business as usual, rather than as a step towards bigger change.

Sharing

Most cars are driven for a relatively short period each day, and are parked the rest of the time occupying land (around 10% in cities). On-street parking eats up large amounts of valuable public space from pedestrians, public transport and cyclists. It’s a wasteful situation, both for the efficiency of cities and for the environment due to the vast amounts of materials and energy used to manufacture our largely idle cars.

One increasingly popular solution in cities is car-sharing, with the largest company Zipcar now up to 700,000 members. Car-sharing is a convenient and affordable option for many city residents who want regular car access without the hassles of ownership. The popularity of smartphones provides an easy way to manage car-share booking. Comparable sharing trends are also evident for ride-sharing and for urban cycling.

Is sharing the answer then to the sustainable city travel? It’s definitely an important trend. Sharing allows a much better pricing model for driving, paying by the mile and charging more at peak times, thus encouraging more efficient behaviour.

Car-sharing coverage is limited however to denser urban areas, and it is not yet clear to what extent car-sharing can significantly reduce the total number of vehicles and car parking space in cities.

Self-Drive

The last trend is at a much earlier stage than electrification and car-sharing, yet it could have the most far-reaching consequences. Sat-nav and parking-assist technologies were early steps towards greater automation in cars. Now Google as well as several manufactures have working prototypes of autonomous or self-driving vehicles.

Amazing yes, but what’s the point? In its current form, the application of this technology is not immediately clear, beyond providing a luxury car gizmo that lets you read the paper while your car drives you to work. But future developments will likely involve cars built around self-drive from the ground-up.

Potentially you could have a city taxi fleet of fully autonomous electric cars, requested by smartphone, operating 24 hours a day, moving to areas of high demand, charging batteries when not in use. Whilst bad news for taxi-drivers, such a system could be highly efficient and provide a quick and flexible complement to mass transit networks.

A related concept has already been developed in a rail-pod form operating at Heathrow airport. Dubbed Personal Rapid Transit, it is intended to combine the advantages of both private and public transport. Obviously the challenges of converting such a system to operate autonomously in the ‘wild’ of the urban environment are many, yet are increasingly being tackled.

If such a system could safely and legally operate, the implications would be massive. Imagine freight and courier services operating automatically at night to minimise disruption; your car picking up your shopping on its own, or taking a nap and waking up at your destination.

Reality Check

It’s easy to get carried away with the wonders of new technology. Transport challenges require political and economic solutions as much as technological brilliance. Indeed relying on car manufacturers alone to green transport is as unlikely as “Beyond Petroleum” BP and Shell delivering the renewable energy revolution. Yet there is some incredible innovation currently emerging, and the next couple of decades are certain to be very interesting times for urban transport.