The Office for National Statistics have started to publish the more detailed tables from the new 2021 census. Of particular interest for my research are the variables related to gentrification. In this post I look at the occupational class data (Standard Occupational Class) to identify areas of London and Manchester with the biggest social changes.

The Changing Geography of London

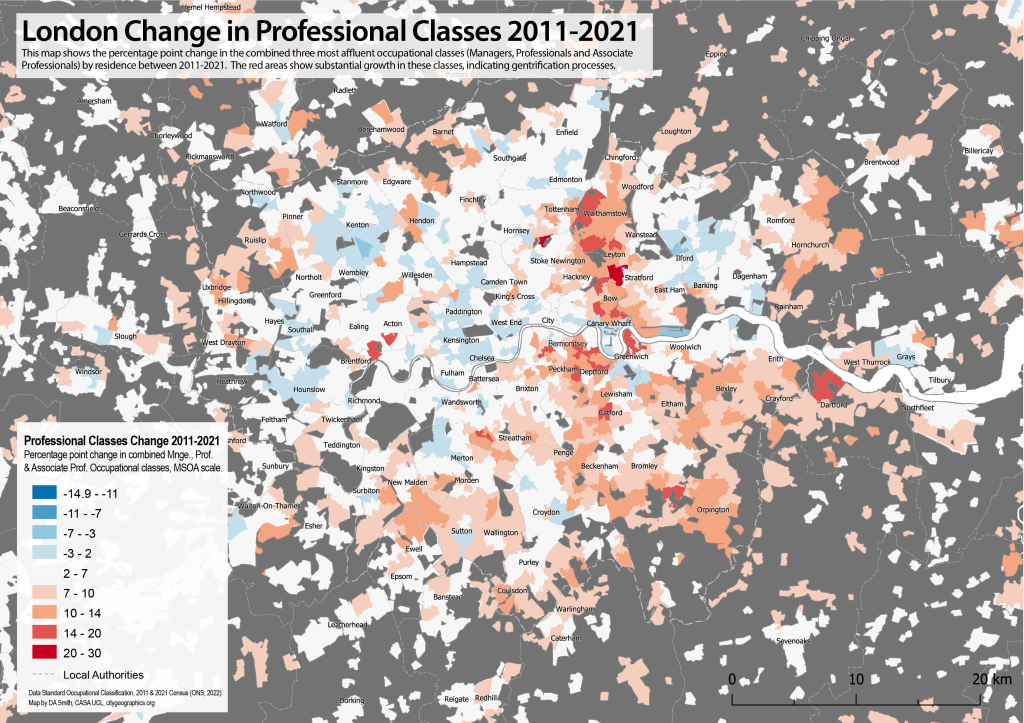

Given that gentrification has been transforming Inner London for over half a century, some researchers had speculated these processes will start to slow with fewer and fewer working class districts left in Inner London that have not already been transformed. The 2021 census data shows however that gentrification has continued at pace between 2011-2021, with substantial changes in the geography of occupational classes, particularly in East and South-East London.

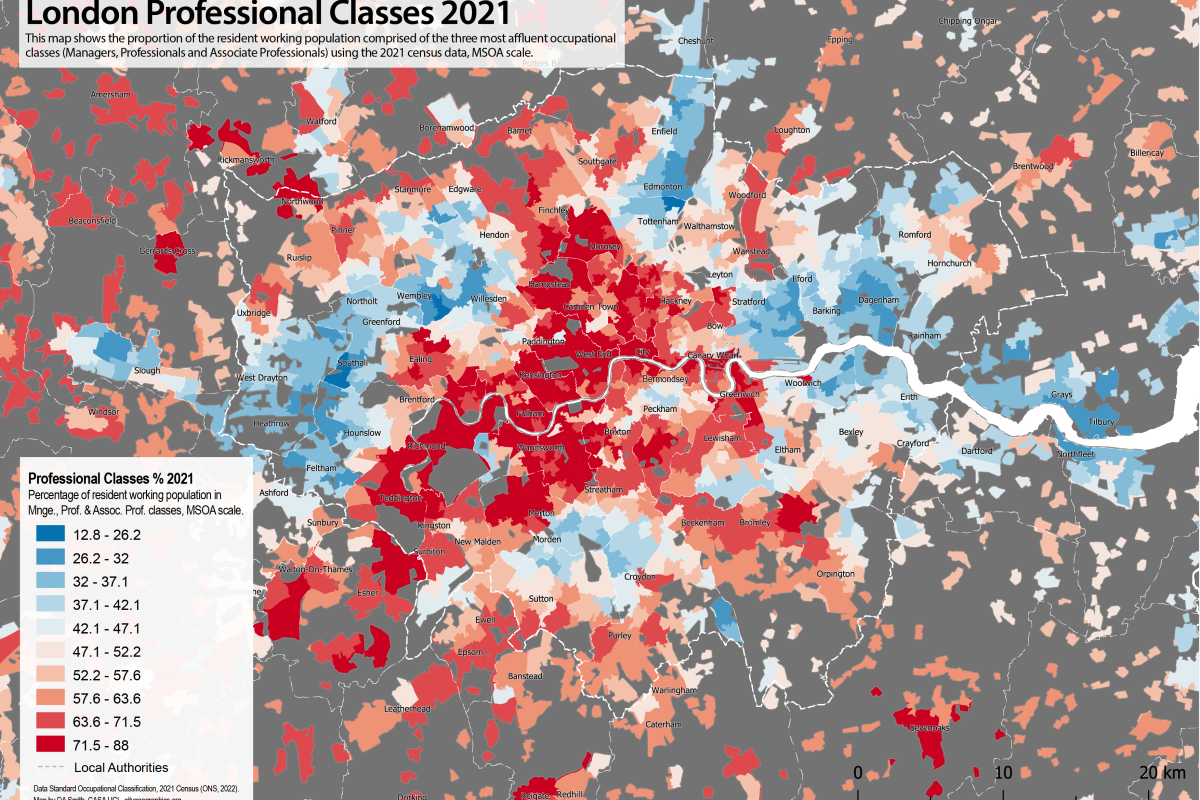

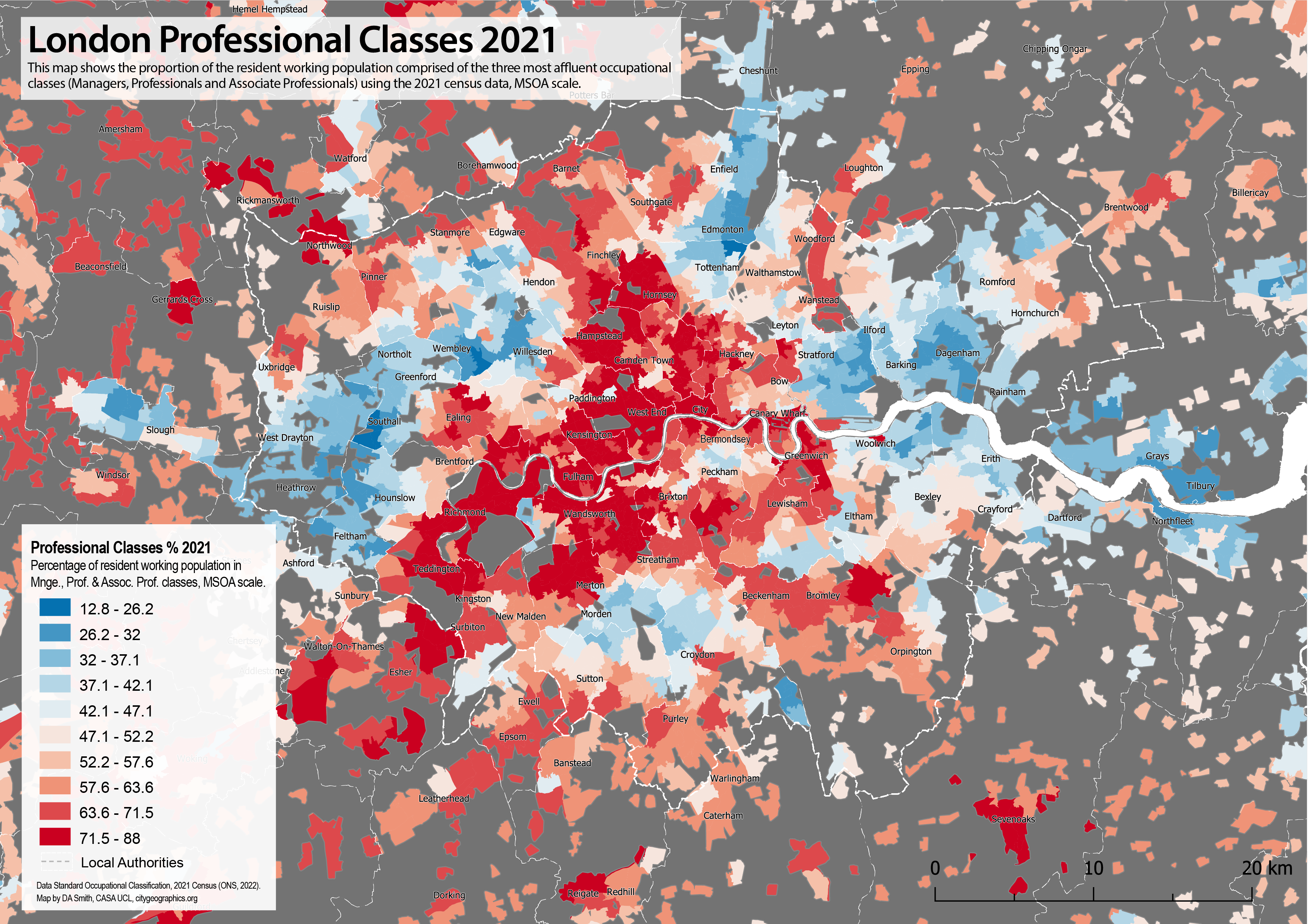

The map below shows the proportion of residents in the three most affluent occupational classes: Managers, Professionals and Associate Professionals in 2021. This is a useful overall indicator of gentrification (though note there are differences between these classes, and deprived populations can also be present in gentrifying areas). The map shows the long established structure of affluent Londoners clustered in Inner and West London, with radial corridors extending South West and North West through historic wealthy areas such as Richmond and Hampstead. The most dramatic changes with the 2021 data are in East London, and South East London, in areas such as Stratford, Walthamstow, Deptford and Greenwich, fitting with widely discussed social trends of these areas in the last ten years. The changes in East London are so substantial that we can identify new radial corridors of relative affluence forming in North East and South East London, mirroring the radial sectors in West London and forming a big red ‘X’ shape on the map. The traditional divisions between East and West are eroding over time with gentrification processes and the substantial transport and planning interventions in East London in recent decades. On the other hand, many of these areas in East and South East London still include high levels of deprivation alongside these gentrification processes, leading to a complex picture.

Below the 2011 and 2021 data are shown side by side with a slider. Gentrification is almost always a spatially clustered process, with newly gentrifying neighbourhoods forming next to existing affluent areas. You can see this very clearly in the maps below as the red areas follow a pattern of organic growth as they expand and strengthen from historic clusters-

We can also map change directly, as shown below. This highlights just how concentrated gentrification is in East and South East London. Some major development sites are picked out, such as the Olympic Park at Stratford, and the developments at North Greenwich. New build gentrification is clearly playing a significant role. But many of the changes are spread across districts such as Walthamstow, Leyton, Bow, Peckham and Deptford, and these changes will be through turnover in the historic housing stock alongside new build housing.

An important difference in 2021 compared the 1990s and early 2000s appears to be more social change in Outer London, at the urban fringe and extending into the more rural Home Counties. This is particularly noticeable in South East London (Bromley, Orpington, Bexley), as well as other parts of Outer London (Barnet, Ruislip, Romford, Coulsdon). This will likely be linked to the extreme unaffordability of Inner London, but the 2021 census may also be picking up some of the demand for larger houses with gardens in 2020 and early 2021 following the pandemic.

On the topic of whether gentrification processes are displacing lower income populations in London, it is not possible to answer with this data. A useful overall perspective comes from looking at the profile of all occupational classes for Greater London in 2011 and 2021. We can clearly observe in the graph below a very large increase in the Professional class, and a big increase in the Management class (Associate Professional is static- this is on average the youngest class, and is probably a sign that this group has been more affected by the price/rent increases). The remaining classes do not however show a decline, they are largely static (except for Administrative, on average the oldest class). This implies that the overall process of increased professionalisation in the last decade has been more about new populations moving to London rather than lower income classes being further displaced, but this conclusion is speculative and migration data would be needed to investigate this. Note also that the professionalisation pattern is clearly visible in the occupational class profile of England and Wales, showing that the growth in knowledge jobs is affecting the entire economy, not just big cities like London.

The Wider Picture Across England

The scale and economic dynamism of London typically makes the capital an outlier compared to other UK cities in terms of processes of urban change. However, devolved governments in city regions such as Greater Manchester and the West Midlands have brought substantial new investment and developments in their cities over the last decade, and we would anticipate some similar processes of social change to be happening. If we look at percentage point change in professional classes for England and Wales (the same measure as the change map above, but this time at local authority scale), we can see the top ranked local authorities are mainly in East and South East London. A crucial difference however is the prominence of Greater Manchester boroughs, including Trafford and Salford. This indicates that major social change is occurring in Manchester. Additionally the West Midlands is also picked up within the top 25 local authorities. Note the national average change in Professional classes is +5.4 percentage points between 2011-2021, so the change towards professional and service jobs is occurring across the economy as a whole.

Local Authorities Ranked by Percentage Point Change in Profess. Classes 2011-2021-

| Rank | Local Authority | Region | Prof. % 2011 | Prof. % 2021 | Percentage Point Change 11-21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Waltham Forest | London (East) | 39.2 | 50.5 | 11.3 |

| 2 | Trafford | Grt. Manchester | 48.1 | 58.4 | 10.3 |

| 3 | Newham | London (East) | 32.0 | 41.5 | 9.5 |

| 4 | Salford | Grt. Manchester | 36.1 | 45.5 | 9.4 |

| 5 | Dartford | London (OMA) | 37.3 | 46.6 | 9.3 |

| 6 | Bromley | London (SE) | 50.6 | 59.8 | 9.1 |

| 7 | Bexley | London (SE) | 36.7 | 45.8 | 9.1 |

| 8 | Greenwich | London (SE) | 44.2 | 53.1 | 8.9 |

| 9 | Lewisham | London (SE) | 48.8 | 57.4 | 8.5 |

| 10 | S. Cambridgeshire | East of England | 52.3 | 60.8 | 8.5 |

| 11 | Stockport | Grt. Manchester | 44.3 | 52.6 | 8.4 |

| 12 | Havering | London (East) | 36.9 | 45.3 | 8.3 |

| 13 | Warwick | West Midlands | 51.9 | 60.1 | 8.2 |

| 14 | North Tyneside | Tyne & Wear | 38.3 | 46.3 | 8.0 |

| 15 | Southwark | London (Inner) | 53.8 | 61.8 | 8.0 |

| 16 | Broxbourne | London (OMA) | 35.2 | 43.2 | 8.0 |

| 17 | Epsom and Ewell | London (OMA) | 51.4 | 59.2 | 7.9 |

| 18 | Sutton | London (SW) | 43.9 | 51.7 | 7.8 |

| 19 | Hackney | London (Inner) | 56.5 | 64.2 | 7.8 |

| 20 | Mid Sussex | South East | 48.0 | 55.7 | 7.7 |

| 21 | Tonbrg. & Malling | South East | 44.1 | 51.7 | 7.7 |

| 22 | Exeter | South West | 39.2 | 46.8 | 7.6 |

| 23 | Bromsgrove | West Midlands | 48.2 | 55.7 | 7.5 |

| 24 | Solihull | West Midlands | 45.4 | 52.9 | 7.4 |

| 25 | N. Hertfordshire | London (OMA) | 49.6 | 57.0 | 7.4 |

| 26 | Sevenoaks | London (OMA) | 48.1 | 55.4 | 7.3 |

| 27 | Epping Forest | London (OMA) | 45.8 | 53.1 | 7.3 |

| 28 | Bristol, City of | West of England | 44.9 | 52.1 | 7.2 |

| 29 | Ribble Valley | North West | 45.2 | 52.4 | 7.2 |

| 30 | Cambridge | East of England | 57.9 | 65.1 | 7.2 |

Occupational Class Change in Greater Manchester

It is clear from the table above that alongside London, there are considerable changes in the occupational class geography of Greater Manchester ongoing. The borough of Trafford ranks second in the above table, while Salford is at four and Stockport at eleven. Repeating the mapping exercise below, we can see that occupational class changes are widespread across Greater Manchester, particularly to the west and south of the city centre. In economic terms this is a positive sign that Manchester’s knowledge economy is growing and attracting skilled workers, an important trend given generally low productivity for many UK cities beyond London. On the flip side however, Manchester residents will be less impressed if house prices and levels of inequality start to resemble the extreme situation in the capital.

We can repeat the change map again for Greater Manchester. Some big development sites appear to be picked up in Salford, Ancoats and Sale (the prominent development site of Salford Quays appears to have already gentrified before the 2011 census). But the growth in more affluent occupational classes is not confined to these development sites, it is occurring across most of Greater Manchester and, similar to London, includes many suburban areas. It is only really in Bolton, Rochdale and Oldham where there are few signs of change identifiable.

Summary

The occupational class data from the 2021 census shows that evolution towards knowledge economy and service jobs continues at pace, with Professional and Management classes showing by far the highest growth levels across England and Wales. London has continued to experience significant gentrification levels, with the spatial focus in the last decade concentrated in East and South East London. London centres such as Walthamstow, Stratford, Deptford and Lewisham have changed dramatically, so much so that we can see two new radial corridors of more affluent populations forming in North East and South East London, mirroring the long established structure of West London.

Gentrification is by no means confined to London, and indeed Greater Manchester has several of fastest gentrifying local authorities in England and Wales, particularly the boroughs of Salford and Trafford. This is largely reinforcing the structure of wealthier populations being concentrated to the south and west of Greater Manchester, and in the city centre.

This analysis has looked only at the new occupational class data, which does provide some interesting insights. To look into these issues more deeply however we would need to add analysis on housing markets, tenure, deprivation, age and migration data.